Art and Artists

Adopt an Old Master

By Matthew Moss, Art Monte-Carlo

Does adopting a picture interest you?

ONCE UPON A TIME THE LOCAL CITY BANK was synonymous with security and prestige. With its reassuring sense of stability and endurance represented by a granite-clad façade sustained by a row of Doric columns, the total encased in a vaguely classical Greek style of architecture. In some of the more venerable institutions the oak-panelled boardroom walls were embellished by portraits of the incumbents’ illustrious predecessors, probably painted by Gainsborough, Raeburn or, even, Van Dyck. It was a time when the working week in the City ended Friday lunch-time

That was all before the Second World War, however. The Victoria-style captains of industry subsequently ceded their thrones to younger men and women much more concerned in winning the conflict against new and faster moving business rivals at home and abroad. One side-effect of this revolution was the necessity of companies to monetise their assets. Down came the non-interest earning gold-framed Sir Joshua Reynolds, John Hoppner and Sir Thomas Lawrence canvases from the Chairman’s office. Standing by, serendipitously, were the big London and New York fine-art auction houses, and the more traditional London Bond Street art dealers like Colnaghis, Wildenstein and Agnews. All were ready, willing and more than qualified to turn the company Old Master into cash. Following the age-old dictum that wealth flows from the weak to the strong, the Sir Joshua Reynolds et al quickly found new homes in other timber-panelled boardrooms, this time in the offices of law companies, management consultants and bankers housed, usually, in skyscrapers in Midtown or Lower Manhattan.

Large art collections are known to have been created from the Renaissance onwards including that of Vincenzo Gonzaga the Duke of Mantua*, later dispersed to pay for the city’s war against an invading French army. The star-crossed Charles I of England bought an important part of the collection**. It, in turn, was broken up after the king was tried for treason and executed in 1649.

Most collectors in the following centuries have recognised that one of the drawbacks fine-art has in common with gold is that it does not generate an income. This becomes most evident in times of crises when collectors need to realise cash by selling their paintings at short notice. It was one of the reasons why, during the forced sale, Cessio bonorum***, in 1656 of Rembrandt’s goods and chattels, assets such as ancient armour and antiques not to mention his collection of paintings and drawings by earlier artists went for pennies on the pounds. Going forward, the beginning of the 2014s found art scholars being contacted with increasing frequency by collectors attempting to locate buyers for paintings they owned and wanted to sell.

Displaying original paintings in decorous surroundings is an important feature of corporate image management. It makes a clear statement to the world about a corporation's cultural identity. Non the less, not every organisation that wants to create an image of exclusiveness can afford to hang or even wants to put Old Master oils on public display. Investing in original art involves also, an important capital outlay for collectors, both private and corporate. The care of works of art includes, in addition, the need to curate the precious pieces, their conservation and restoration and some high insurance premiums against theft, damage or loss.

So it is that some institutions, possessing champagne tastes when it comes to the arts while at the same time having beer-sized budgets eventually, starting in the mid twentieth century, began to adopt rather than buy Old Master paintings to adorn their walls.

The Midland Health Board a government funded public-health management agency in the ancient Irish midlands town of Tullamore, County Offaly, is the earliest documented and was also the most long-lived example of an Old Masters collection adoption. Tullamore was also home to the legendary Tullamore Dew whiskey. The collection contained original paintings by Jan Breughel de Velours, Richard Wilson and other mostly Northern European original Old Masters. From 1973 onwards, known as the Tullamore Old Master Museum, it became available to viewing by the public and represented an important cultural asset for this region.

In 2008, Ireland experienced the first symptoms of a property market crash. Government revenues, dependant almost entirely on this sector, experienced a marked decline and banks suffered severe liquidity crises. Reflecting the drop in the government’s revenue County Tullamore, found it increasingly difficult to support their adopted Old Master Museum. It closed its doors in May 2012.

One of the most successful projects for allowing the public to adopt Old Master paintings was begun by the Victoria Art Gallery, in Bath, Somerset in the UK.

Adopted painting from Victoria Art Gallery in City of Bath,

Somerset UK, hanging in the Register Office.

A spa city, it was a centre of portrait painting in the late 18th century when Thomas Gainsborough and JMW Turner were active there.

The adoption project’s continuing success was achieved by the use of a genial concept; create a symbiosis that privileged the art lover’s wish to possess, for a time, a work from the collection and, equally, the practical conservation and preservation of the museum’s masterpieces. The individual or organisation would take one of the museum’s artworks under their wing and contribute an often modest figure towards the restoration of the work of art or indeed, its ancient gilt frame alone. In the museum’s restoration laboratory paintings conservators would begin removing old repaints and darkened varnish and discreetly inpaint missing areas of the paint layers. Finally, upon completion, the privileged benefactor could hang a recognised work of art on the walls of his public or private premises for a year.

Another European institution that has successfully practiced the art of allowing the public to adopt an Old Master is the Dulwich Picture Gallery in South London, England's earliest public art museum. The programme began in 1988.

|

|

|

|

Rembrandt van Rijn, portrait of Jacob de Gheyn III,1632. 29.9cm x 24.9cm, Oil on oak panel. Dulwich Picture Gallery, South London., UK

This particular Rembrandt has entered the Guinness Book of Records for having been stolen from Dulwich picture Gallery on four different occasions, a world record. |

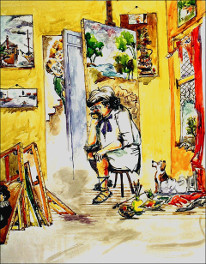

“Poor Rembrandt, they stole everything he owns but ignored his paintings. “ Rembrandt in the midst of the desolation caused by burglars who stole everything in his studio but ignored his paintings. |

Besides offering the donor the right to visit the conservation laboratory, the donors name also appears on the picture label attached to the wall of the art museum. In addition the donor participates in a private vernissage when the restored painting formally takes its place amongst the other art works on the museum’s walls. The opportunity to use an image of the painting as a greetings card, without the requirement to pay the normal reproduction license, is probably of more value to institutional patrons.

Similar arrangements to allow private and institutional art connoisseurs to adopt paintings are prevalent in United States art museums. However, they would more correctly be labelled as, long- distance adoption in this instance. The adoption gives the art lover the privilege of becoming directly involved in the conservation of a painting. This can be of great help to a local art museum where an important painting may lie neglected in the museum’s storage area through the absence of the financial means to halt its ongoing degradation or the possibility of putting it on view to the public in good condition.

The benefactor, in this instance, identifies more closely with the work of art he has adopted through an active and ongoing dialogue with the museum curator and the painting’s conservator. He will receive regular updates and progress photographs of the painting during its restoration. American fine-art institutions do not loan out the adopted painting to donors; they do, on the other hand, have a valuable fiscal advantage in that, by adopting a work of art the donation is tax deductible.

One explanation for the emergence of picture adoption from the second half of the 20th. century onwards is the accelerating scarcity of Impressionist and Old Master paintings coming on to the market. On 29th. January 2014 Christie's put up for sale a canvas by Artemisia Gentileschi,**** a respectable Baroque painter, Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, in their Old Master painting's sale at New York’s Rockefeller Plaza. It was expected to fetch between three and five million dollars. In the end, however, it remained unsold at two million. Notwithstanding this, it was a figure still out of the range of many private and business collectors.

One logistical problem that a fine-arts institution encounters when arranging to put a painting up for adoption is its ecological footprint. The Victoria Art Gallery in Bath, for example, is happier if the potential benefactor resides within a 24 kilometre radius of Bath. Notwithstanding these various bumps in the road, adopting an original painting is still a useful amenity. Thus, private and corporate collectors in the Principality of Monaco, Provence-Côte d’Azur, the Italian Riviera and Northern Italy can avail of fine-art adoption services. A remark, true at the time and still valid today once made by Thomas J. Watson, Sr., the founder of IBM, “ the increased interest of business in art, and artists, is to their mutual benefit”.

Rembrandt needs help handling his workload

now that everyone thinks he’s dead.”

The premature announcement of his death compels Rembrandt to work overtime due to the resulting increased demand for his paintings.

http://rembrandt.ie/index.php?page=adopt&id=56

FOOTNOTES

* Vincenzo Gonzaga the Duke of Mantua 1562 –1612 was the first major patron of Peter Paul Rubens

**One of the king’s paintings ended up, eventually, in Townsville, a township on the Great Barrier Reef, Queensland, tropical Australia.

***Cessio bonorum*** A voluntary bankruptcy of Roman origin, that allowed Rembrandt to voluntarily cede all his property to his creditors and avoid jail.

****Artemisia Gentileschi, (1593-1652/3)

An extended version of this article can be found on the Art Monte-Carlo Blogs page.

If you need an appraisal of your old painting, contact Matthew Moss at Free Paintings Evaluation.