General Articles

Unsung heroes: The faces of the refugee crisis

By Indie Publisher and Author, Melissa Roen

In the middle of December, during Syrian President Assad and his allies’ final assault on the last opposition stronghold in eastern Aleppo, the gruesome images of the dead and dying, lying in the rubble of shattered streets, were in stark contrast to the holiday lights and good cheer that were, at the same moment, ubiquitous throughout the western world. Particularly, the photos of women and children trapped between the opposing forces in the bombed-out ruins of Aleppo, were a sickening reminder that the magic of Christmas doesn’t come for every child.

One look at the haunting photos of their innocence forever extinguished by the government forces’ relentless bombardment of their homes, or the glazed eyes staring back in incomprehension as to why these horrors had been visited upon them, should be enough to convince anyone--with an ounce of humanity in their hearts--no one, anywhere, should endure such punishment.

In the days leading up to Christmas, the headlines screamed of the pro-Syrian regime forces’ savagery and the meltdown of humanity in Aleppo: people shot in the streets, while trying to flee the fighting; others executed in their homes by regime forces, because they had the misfortune to live within the rebel stronghold in eastern Aleppo.

In vain, governments and world leaders protested the slaughter of Aleppo’s civilians. As reported in The Guardian, “We’re seeing the most cruel form of savagery in Aleppo, and the regime and its supporters are responsible for this,” Turkish foreign minister Mevlüt ÇavuÅŸoÄŸlu said, adding that: “The wounded are not being let out and people are dying of starvation.”

Meanwhile, according to the same article reported in the Guardian: “Russian foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, said Moscow was fed up of calls from the US to halt the fighting. “We are tired of hearing this whining from our American colleagues in the current administration,” he told journalists.

In a cynical attempt to manipulate public opinion and distort the world’s perception of reality, Putin TV attacked the accounts of the barbarity and slaughter perpetuated by Russian ally Assad’s pro-regime forces as “Fake News” being spread by western liberal media.

No, Christmas didn’t come to eastern Aleppo, in 2016. No matter how much Putin would like to label it Fake News, the raw video feeds coming out of Aleppo, were more like a preview of the coming Apocalypse… The migrant crisis in Syria won’t end with the rebel forces’ defeat in Aleppo, nor ISIS’ defeat in Mosul, or any of the less-publicized wars across the globe. Instead, it will bring a new cycle of thousands upon thousands of displaced civilians, fleeing the total destruction of their world. When the weather turns more clement, the trickle of refugees will—once again--become a deluge.

Meanwhile, the tragedy of Aleppo is off the front pages in in the western world. Until the next slaughter of innocents; the next inhuman war…

Every time there’s a new headline about the latest humanitarian crisis, many of us post on our social media pages heart-rendering images, and articles detailing the horrific events in solidarity with the defenseless victims; in shock and outrage at the casualties of another senseless war for profit. We aren’t indifferent to the humanitarian tragedy thousands of miles from our home--in another world, on another shore. Especially, when a humanitarian crisis arrives on one’s doorstep, the toll of human suffering can no longer be ignored.

In the Italian frontier town of Ventimiglia, and to a lesser extent in the Alpes Maritimes, the refugee crisis touches many inhabitants, on a daily basis. The politics surrounding the crisis has created a polemic with feelings, on both sides of the issue, running high.

Granted, there are no easy answers to such a complex dilemma. The flood of refugees from strife-torn nations has overwhelmed certain frontline countries in Europe, such as Greece or Italy, whom are ill-equipped to handle such a large influx as they struggle under the burden of their own economic crises and citizens in need. Other countries that have historically large immigrant populations, such as France and Germany, are facing presidential elections in 2017, and embroiled in fierce internal debates concerning national identity and political direction of their respective countries, while populism stampedes across the European continent. The U.K. decided on which side of the immigration question they stand, with their vote for Brexit. Trump recently signed an executive order banning refugees from many of the worse hit countries from entering America.

However, while the polemic rages and politicians campaign, non-governmental organizations, church-affiliated charities and private citizens in France and Italy fill the void of governmental inaction, by creating their own networks and grass-root initiatives to help with the local refugee crisis on the Italian-French border.

While the number of refugees on the Italian border has considerably dwindled this winter, a new tide of displaced persons will most likely follow in their footsteps in 2017. Ventimiglia is a way station: one more stop on their journey to find asylum in France, or in northern Europe. No matter how perilous their quest, the difficulties involved in rebuilding their lives in a new country, what awaits them if they’re deported back to their own homelands are war, starvation and death.

The faces of the refugee crisis in Ventimiglia:

In the summer of 2016, I read numerous articles concerning the refugees camped across the border in Ventimiglia, and the political discourse—both pro and con—surrounding the situation. However, the urgency of the crisis was brought home to me, on a human scale, when I read a post on a friend’s Facebook page, dated July 3, 2016.

Victoria, a local woman living in the Monaco area, described how, on a family outing across the border in Italy, she came face to face with the following:

“Monaco friends please help!! I happened upon a spot today between Latte and the French Border where there are many refugees with nowhere to go and nothing to sustain them.

I am going to try and fill my Q7 to the brim with anything and everything I can find to take to them. I am asking for donations of anything you would like to donate. I'll come pick it up. I will take it to them Tuesday. We live too close to not help them.”

A simple message, but Victoria’s heartfelt words summed up the stark reality co-existing, scant kilometers away, with the privileged life that so many of us lead on the Côte d'Azur. Subsequently, I contacted Victoria to learn more. I had no personal belongings to donate that would be appropriate for the refugees’ situation, but there existed an urgent need for basic foodstuff, personal hygiene products and clothing. I went to Carrefour and stocked up the required items. Victoria came the following day to pick up my donation to deliver to the refugees in Italy.

Since this day in July, Victoria has created awareness within the Monaco community concerning the crisis on our doorstep and, on a weekly basis, picks up donations from local residents to deliver to the refugee distribution and reception center run by Caritas Diocese Ventimiglia. Because of caring personal initiatives, such as Victoria’s and other volunteers and organizations, the refugees’ basic needs are met, while daily acts of human kindness help to alleviate the misery and uncertainty during their stay in Ventimiglia.

I’ve since discovered that like-minded people, in the Alpes Maritime, have created their own grass-roots initiatives. One such private group on Facebook, Refugee Aid Côte d’Azur, which was founded in September 2015 and counts 1300 + members, has banded together to create a network of private citizens, who share valuable information concerning the refugees needs and collect donations to deliver to the Caritas refugee center in Ventimiglia. www.facebook.com/groups/431514883706994

Sadly, there is no official governmental help for the refugees blocked in the bureaucratic limbo of the Italian/French border. A press release from Caritas Europe, dated July 7, 2016 described the urgency of the refugee crisis in Ventimiglia in the summer of 2016:

“Migrants, mostly Sudanese, Eritreans and Ethiopians, arrived from Sicily to Ventimiglia with the hope of continuing their journey to France and northern Europe. However, they were blocked at the border between Italy and France. Stuck in Ventimiglia, with no access to any type of services or any proper reception centers, the families, pregnant women, children and babies are forced to sleep outside.

On 31 May, Mons. Suetta opened the church Sant’Antonio to provide a safe haven for 5,000 exhausted migrants, a place of respite for the people before they reattempt to cross the border…”

Un Geste pour Tous (French NGO) is another group who works closely with Caritas in Ventimiglia. Founded in 2014 and based in Nice, their principal focus is humanitarian crises on the international stage. During 2016, they’ve sent three, separate convoys to Syria’s citizens devastated by war: filled with donations of clothing, food and medical supplies collected from local charities and individuals. Un Geste pour Tous, also, runs an initiative in Nice, through volunteers and donations, to help the homeless and local population in need:

www.association-ungestepourtous.org

On February 15, 2017, will be held a conference on the world-wide refugee crisis: “Grande Conference sur la Crise des Migrants” at the FAC de Lettre campus, Nice Sophia Antipolis. www.facebook.com/events/1824916021130645/

A roster of notable speakers will be present at the Grande Conference sur la Crise des Migrants, including Pierre-Alain Mannoni. Professor at the university of Nice, Pierre-Alain Mannoni was recently acquitted of abetting illegal migrants, for transporting three Eritrean refugees (unaccompanied minors) from the Italian border. The Tribunal Correctional in Nice vacated Mannoni’s charge as under French statute a person may be granted humanitarian immunity for coming to the aid of someone in dire need. The case doesn’t end here as the French public prosecutor’s office announced they will appeal the verdict.

However, Mannoni isn’t the only French citizen tried by tribunal in Nice for providing succor in times of hardship and distress to an illegal migrant…

The Roya valley is a clandestine entry point for refugees in France. Since the Bastille Day terrorist attack, French governmental authorities have made securing the nation’s borders a top priority and repulse refugees’ attempts to enter French territory on public transportation. Consequently, the refugees try to circumvent this edict by following the railroad tracks, on foot, through the Italian mountains that lead to the Roya valley.

Many of the people undertaking this dangerous trek are unaccompanied minors: exhausted, hungry, frightened and woefully ill-prepared for the rigors of winter in the lower French Alps. One might think the culture differences would be too vast to bridge, between a rural, mountain community and clandestine migrants from Africa and the Middle East. However, the outpouring of help and solidarity shown for the refugees, who have succeeding in crossing into France via the Roya valley, is nothing short of inspirational.

Make no mistake: aiding illegal migrants on French territory, whether it be providing food and shelter, transporting them in your vehicle--or even an action as innocuous as being in their company--can expose an individual to judicial and penal pursuit. Members of the collective, Roya citoyenne, who are instrumental in providing aid and advocate for migrants, have been charged and brought before the tribunal in Nice for providing such humanitarian aid. www.facebook.com/royacitoyenne

One such citizen, Cedric Herrou: a farmer in Breil sur Roya, has been charged, on three separate occasions, with aiding unaccompanied minors, who have illegally entered French territory. His confrontations with the French judicial system have become a local “cause celebre.” In two instances, the charges against him have been dismissed under the statue of humanitarian immunity. His most recent trial at the Palais de Justice in Nice on January 4, 2017, drew a crowd of more than two hundred of his supporters. The verdict will be pronounced on February 10, 2017.

Bane of the French authorities, or unsung hero? It depends on who you ask. Cedric Herrou: protector of illegal migrants, was recently voted in December, by Nice Matin’s readership (55% of votes cast) as their choice for L'azuréen de l'année 2016.

* * *

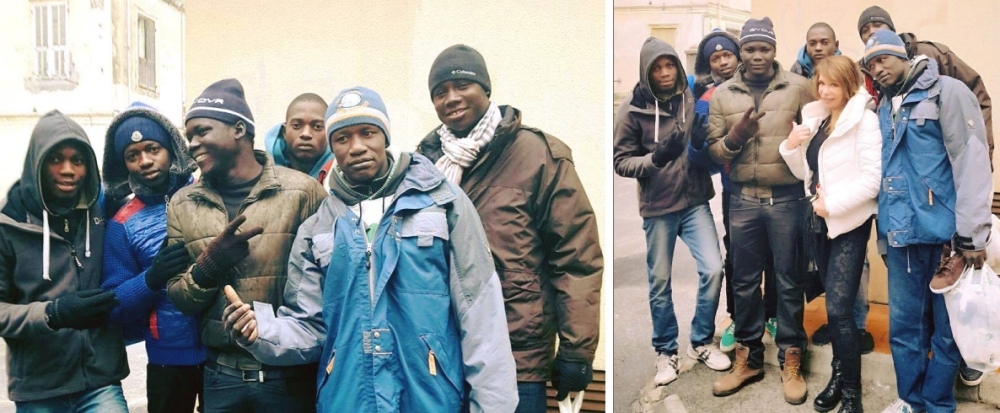

It’s a gray morning in early January: menacing rain clouds and a cold wind that bites to the bone, when I accompany Victoria to the refugee center in Ventimiglia. She’s the perfect guide. Since the height of the crisis last summer, Victoria’s made bi-weekly visits to Ventimiglia, working alongside the Caritas volunteers.

Our first stop is the UPIM: five hundred meters from the Italian border crossing. We’ve a shopping list, provided by volunteers at Caritas, of the most immediate needs: warm gloves, woolen ski hats, shoes for men and 5-euro phone cards (so they can communicate with their families back home.) There are mostly young males--many, unaccompanied minors--at the refugee camp in January. At present, Caritas isn’t accepting donations of winter clothing for women and children as storage space is limited; they have sufficient stock to meet any immediate demand. Their website regularly lists priority needs.

www.facebook.com/ventimigliaconfinesolidale

However, Victoria has promised a young mother, with whom she’s in close contact, that she’ll bring warm clothes for her baby. Although, I’ve already emptied the aisles at Decathlon in Monaco for gloves and hats, while Victoria shops for infant clothes and shoes for her friend, I take advantage of the cheaper January sale prices in Italy to stock up on more gloves, hats and a few pairs of men’s shoes. I finish first and wait for her outside by the entrance, where I notice a youth, without gloves, sheltering from the cold on the adjacent stairs.

I offer him a pair gloves; ask his name; what country he’s from. He’s seventeen years old; from Nigeria. I inquire where he sleeps at night. His reply: on the beach, with no shelter. An icy wind swirls through the dank parking structure, while we talk. I can only imagine how brutal it must be at night with no tent or sleeping bag to keep warm. Victoria joins us and I relay our conversation. I see the anguish this news costs her. A mother of five, Victoria’s compassion embraces every soul who crosses her path. She immediately shifts into action and informs him that Caritas is distributing sleeping bags. She knows of which she speaks: a few days before, Victoria delivered one hundred new sleeping bags to the center…

As we drive the short distance to the center, Victoria speaks candidly of her experiences as she waves to each group of refugees we pass, en route towards the distribution center. She recognizes many of them on sight, and knows their back stories: which country they’re from; how long they’ve been in the camp. We pass the church of Sant’Antonio, which provides a daily hot meal for those in need, before turning down the alley to the center.

I take in the surroundings as we wait for the gate to open. The bleak setting of old buildings is transformed by the smiles of the Italian volunteers who greet us and help unload the car. We climb the rusting stairs to the upper level, passing a group of three women, sorting an enormous mound of donated clothes. Victoria introduces me, and has a kind word for everyone we pass. I can tell she feels at home here. More introductions, a brief tour of the center and an offer of coffee follows.

While Victoria shows the baby clothes to the young mother in a room inside the center, she suggests I hand out the gloves and hats I’ve brought to the people waiting in line. Everything is organized efficiently. A table has been set up on one side of the building, with clothing ready to distribute. I leave half of my shopping bags with the volunteer manning the table.

This morning, about thirty young men wait patiently for their turn; a slip of paper in hand, with their name and a box to tick next to each item listed: from hats, gloves, pants and coats to underwear, socks, shoes, or personal hygiene products they may need.

I move down the line, asking if they need gloves or hats. I ask each one where they’re from. They answer: Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria, Iraq. Some speak a few words of English or Italian; others French. Somehow, we communicate. Everyone I speak to is polite, patient and appreciative. Even under such wretched circumstances, no matter what trials they’ve endured to come this far, there’s a kind of stoic dignity about them that belies their young years.

The first bags empty quickly and I retrieve two more. The line lengthens as more people arrive. I’m almost to the end of the line, when I notice a boy without socks, wearing rubber thongs. A light drizzle—almost a mist—begins to fall: making a gray and cold day, even more miserable. Luckily, one of the new trainers that I brought is his size. His friend’s shoes are in tatters; I don’t have his size. A young man, a few paces down the line, can use them.

Next is two newly arrived refugees from Iraq: wearing summer board shorts and shivering under blankets wrapped around their shoulders. On their feet, no socks and rubber beach thongs. I don’t have any shoes left. Even though they must be freezing in such a state, they’re smiling and friendly. One speaks perfect English. He recognizes my American accent and wants to know more about California.

Victoria joins us, sizes up the situation and takes control. All around us are boys and young men in worn out shoes with holes; some, several sizes too large, others have squeezed their feet into shoes that are too small. Their feet must be sore and ache after all the miles they walk every day, in ill-fitting shoes, from their camp on the outside of town to Caritas. For Victoria, this will, absolutely, not do. There’s nothing for it, but a trip to UPIM to buy shoes for the boys. As we talk, a small crowd gathers around us. We start taking orders for shoe sizes from the ones in need: twenty in all. Victoria tells them to wait. We’ll be back shortly with new shoes and socks…

Forty minutes later we’re back; the youths patiently waiting for us on the street, outside the entrance to the center. I’d worried that they might have given up and left. But they trusted we would keep our word.

Handing out twenty pair of shoes and socks goes quickly. We chat a few minutes more as Victoria notes which items any of her boys might need. We say our goodbyes. Victoria promises to be back on Friday.

Back on the autoroute, we head towards our homes on the French side of the border. A harder rain begins to fall, but we’re snug and sheltered in the heated car. I think about the people I met today: the volunteers at Caritas, selflessly working to bring a ray of hope and a measure of care into unfortunate lives.

I think of the “refugees” I met this day. They’re no longer some abstract statistic for me. I’ve seen their faces; spoken with them; looked in their eyes and touched their hands. They’re flesh and blood human beings, the same as you and me. How can one blame them for fleeing death and destruction? Would we not do as they—choose life over death--if faced with the same choice?

In the days that follow, as a vicious cold front descends on our region, I continue to think of the people I’ve met in Ventimiglia. I still see their faces; their stoic dignity in face of adversity. While the temperature plummets at night: safe in my warm bed, I hear the wind and rain lashing the tree outside my window and imagine the youth from Nigeria, sleeping on the beach this freezing night with no shelter. How can he, or any of his friends, survive nights such as these? What will happen if they fall sick, with no one to take care of them—so far from their families and home?

One thought stays with me. It keeps playing over and over in my head:

I wish there were more I could do to help them…

What Caritas Europa, Caritas Italy and Secours Catholique-Caritas France are urging the EU and the Italian and French authorities to do:

-

Provide for the basic needs of migrants, including those in transit, to guarantee their human dignity and refrain from using arbitrary detention or arrest;

-

Guarantee solidarity and responsibility-sharing among EU Member States and between the EU and non-EU countries; Italian and French governments must agree on a common response to the situation, respecting the fundamental rights of migrants;

-

Give priority to protecting people instead of protecting borders, with particular attention to women and children;

-

Open more safe and legal paths to come to Europe.

â¤

Melissa Roen has published two novels and in two languages, her native English and also in French: 'Last Call for Caviar' and 'Maya Rising'.

Visit website: www.lastcallforcaviar.com

Visit Facebook: www.facebook.com/Last-Call-for-Caviar

Media Kit: www.lastcallforcaviar.com/assets/media-kit-en.pdf

See also on The Riviera Woman:

Melissa Roen - The Indie Publisher Experience

Melissa Roen Reflects... Satire, Shakespeare, Another US Election

Melissa Roen - Sexy Beasts and Beautiful Creatures: How to write a sizzling sexual scenario