General Articles

(Art)Transportable Wealth

Taking it with you

You may have an old oil painting or a family portrait in your home that has cheerfully hung there both ignored and unnoticed by everyone for generations. Apart from being an important family document or a pleasing work of art, a painting can be valuable in other unexpected and curious ways.

Amongst the landed gentry of earlier generations Old Masters were a reliable way of raising money. One sent the painting up to a London salesroom, discretely, and replaced the original with a copy. The strategy was useful as it avoided suspicion that circumstances were forcing one to dispose of family heirlooms.

Horace Walpole’s nephew in 1779 similarly disposed of one of the greatest eighteenth-century collections of paintings in England at the time, accumulated by him and his father, Robert Walpole the British Prime Minister. He sold the 198 canvases to the Russian royal family amongst which were three important Poussin’s that are today in the Hermitage.

In the nineteen seventies the author visited the seventeenth-century collection of full-length family portrait paintings by, amongst other Old Masters, Sir Peter Lely and Anton van Dyck in the Georgian villa of an old Anglo-Irish family in Mallow, county Cork. What he discovered instead, was a collection of late nineteenth century copies, the original Old Masters having previously been secretly disposed of.

Valuable paintings are occasionally useful for keeping your wealth from the indiscreet eyes of various tax authorities. Calisto Tanzi was the CEO, of Parmalat an Italian multinational corporation that, in 2003, acquired the doubtful honour as Europe’s largest bankruptcy. The giant dairy and food group lost 14 billion euros. Sig.Tanzi arrested for financial fraud and money laundering was sentenced to 10 years in prison. While appealing the sentence rumours circulated in Italy that the apparently impoverished Calisto Tanzi was concealing a treasure trove of valuable works of art and trying to get them into Switzerland.

Eventually, 5th December 2009, nineteen paintings including Cezanne, Monet, Degas, Picasso secreted in the cellars of various family-owned apartments were discovered by the Italian courts. Although the customs authorities knew of a further 23 valuable paintings, amongst them a Manet and a work by the Italian futurist Balla having discovered that they were listed on an insurance policy, the paintings themselves were never found. There were some obvious forgeries amidst the paintings recovered and these may have been painted to replace original works he had already sold or had been spirited out of Italy.

When the Soviet Union, with the fall of Berlin, gained political control of Eastern Europe in 1945 families great and small saw what now remained of their property, land and businesses that had survived the war nationalised. In the great migrations of families westwards most had to leave everything they owned behind. Old family paintings were often a useful store of value they could carry and helped many families survive. Paintings could be concealed relatively easily and if on canvas rolled up and pass through frontiers undetected. Once out of danger the refugee could unroll the canvas, attach it to a new support and, after some minor restoration to repair damage the painting’s sale would help them survive.

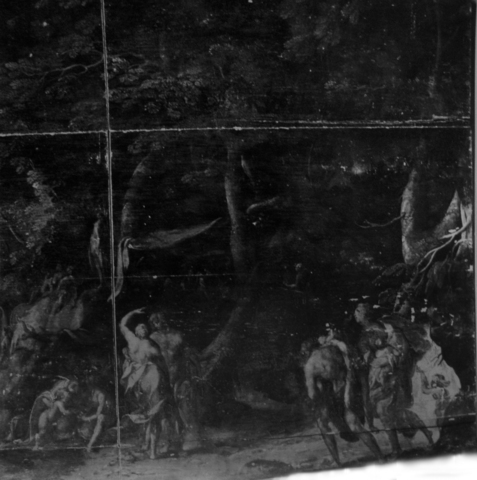

The most curious post-war art-smuggling example your author encountered was in the old gold-mining town of Ballarat in Australia. A Czechoslovakian family escaping from their homeland after World War ll managed to flee with a large painting, a Fête Champêtre painted by a Flemish 17th century mannerist artist. The family’s particular difficulty was how to transport an Old Master that was painted onto a large oak panel. Unable to roll up this particular work of art, the owners resorted to sawing the timber on which it was painted into six separate pieces, and, in fact, it travelled quite successfully out of the eastern bloc. When the family finally came to rest safely in Australia their sawn-up work of art created a particularly interesting and unusual conservation project.

Most old paintings done before 1850 are considered Old Masters so, reasonably, if you possess an oil painting painted before that cut-off date you own, by definition, an Old Master. Old paintings are frequently unsigned and this will not necessarily diminish their value. Your work of art may be a fragment of much larger canvas and the signature have been on the part that was discarded. Signatures were easily removed inadvertently in earlier times during restoration or, simply, the artist did not sign the painting. A signature is, in addition, an unreliable source of authenticity as it can too-easily be forged.

A genuine signature can, on the other hand, be valuable in establishing an artist’s unique style and distinguishing him from his contemporaries his followers, or from imitators. The Dublin National Gallery’s David’s dying charge to Solomon is a large 17th century canvas signed by the Dutch artist Gerrit Willemsz Horst. During the course of the painting’s restoration by the author and his équipe it was noticed that Horst’s signature had, instead, been added in the nineteenth-century, three hundred years later. Removing the false signature we found that concealed beneath, was another this time original. It was by Ferdinand Bol a contemporary of Horst and one of Rembrandt van Rijn’s better pupils. The discovery is a good example of how a Dutch master like Ferdinand Bol whom we would today regard as important had, in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, fallen into oblivion and his signature replaced by that of an artist by then regarded as more valuable.

David’s dying charge to Solomon Ferdinand Bol, 1616 – 1680 Dublin National Gallery

More recently, the author examined a painting that a lady, a resident on the Riviera, had bought at a local auction. The painting–a head and shoulders portrait of a noblewoman–was cut down from a full length canvas and, obviously, not signed. It appeared to be, on the other hand, a genuine work of the 17th century Italian school. On the old worm-eaten wood stretcher onto which the canvas was nailed, we discovered an old inscription written in pen and ink. The legend, in an old-fashioned calligraphic style, attributed the portrait to Lavinia Fontana. Lavinia was an important female painter of the School of Bologna in Italy. Between 1552 and 1614 she was much sought after by the aristocracy of her day for her skill in painting portraits.

The inscription on the timber frame appeared genuine and the style of the painting was consistent with the type of works artists were producing at that time. The fortunate collector had acquired, as a result of this simple discovery, a work of art of some importance and uncovered a work of a once forgotten important female Old Master. In short, it might well pay, after all, to have another look at some of those dull and dust-laden old family paintings that you have tucked away.

Your correspondent will give a free evaluation of one old oil painting in your possession at Free Paintings Evaluation

Dismembered Flemish Old Master Panel Painting.

Dismembered Flemish Old Master Panel Back.